As I learned from an article off of Power Line earlier this morning (my time), back in 2007 the Wall Street Journal published a superb op-ed on Memorial Day from an author and historian named Peter Collier. It can be found in full here.

The article is a timely reminder of what Memorial Day means to Americans, and why it is so important to the very concept of America as a nation:

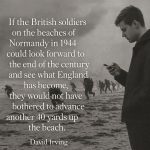

Once we knew who and what to honor on Memorial Day: Those who had given all their tomorrows, as was said of the men who stormed the beaches of Normandy, for our todays. But in a world saturated with selfhood, where every death is by definition a death in vain, the notion of sacrifice today provokes puzzlement more often than admiration. We support the troops, of course, but we also believe that war, being hell, can easily touch them with an evil no cause for engagement can wash away. And in any case we are more comfortable supporting them as victims than as warriors.

[…]

Several Medal of Honor recipients told me that the first thing they did after the battle was to find a church or some other secluded spot where they could pray, not only for those comrades they’d lost but also the enemy they’d killed.

[…]

One of Mr. Thorsness’s most vivid memories from seven years of imprisonment involved a fellow prisoner named Mike Christian, who one day found a grimy piece of cloth, perhaps a former handkerchief, during a visit to the nasty concrete tank where the POWs were occasionally allowed a quick sponge bath. Christian picked up the scrap of fabric and hid it.

Back in his cell he convinced prisoners to give him precious crumbs of soap so he could clean the cloth. He stole a small piece of roof tile which he laboriously ground into a powder, mixed with a bit of water and used to make horizontal stripes. He used one of the blue pills of unknown provenance the prisoners were given for all ailments to color a square in the upper left of the cloth. With a needle made from bamboo wood and thread unraveled from the cell’s one blanket, Christian stitched little stars on the blue field.

“It took Mike a couple weeks to finish, working at night under his mosquito net so the guards couldn’t see him,” Mr. Thorsness told me. “Early one morning, he got up before the guards were active and held up the little flag, waving it as if in a breeze. We turned to him and saw it coming to attention and automatically saluted, some of us with tears running down our cheeks.

I have excerpted from the article purely for the sake of brevity, but every last word of it deserves to be read and digested and understood.

Back when America was a nation, it was great because it was profoundly good. And, to the extent that America still is a nation, it is so because it understands that its existence depends on paying the highest possible price to secure the freedoms and privileges that its peoples enjoy.

It is a uniquely American characteristic to revere and respect their war dead in the way that they do. Other nations certainly have similar remembrance ceremonies. The British wear poppies to remember their war dead. The Russians honour their own dead – millions of them from both World Wars, and a thousand other conflicts besides – in typically grandiose and powerful fashion on both Defender of the Fatherland Day in February, and Victory Day in May. The Germans are much more subdued about such things, mostly because they have had all sense of nation and national pride thoroughly beaten and humiliated out of them.

But the American way of honouring the fallen is unique, and uniquely powerful.

Memorial Day is a harsh reminder for all Americans, should they choose to accept it, that the freedoms that they love so much, and love to talk about, must be secured with the highest cost possible. While the wars fought by Americans over the past twenty years or so have certainly put that idea to the test – since not one of them involved fighting against an enemy that truly and seriously threatened American freedom and sovereignty, not even in Afghanistan, and every single one of them has resulted in absolutely pointless and futile nation-building exercises that have failed miserably – the fact remains that Americans today live in freedom because nobody dares to mount a serious attack or invasion of the sovereign territory of the United States of America.

Why?

Because over a million American war dead, accumulated through more than two hundred and forty years of existence as a sovereign power, were used in conjunction with America’s vast natural wealth and geographical separation from virtually all possible hostile powers to defend their homes, families, and nation.

As we watch the American nation falling apart before our eyes, as we see the breaking that some of us have talked about and feared for so long coming to pass, as the “American” people self-segregate themselves into mutually exclusive and extremely hostile armed camps, it is worth looking back and remembering that there was a time when Americans were one people with a common heritage.

And that heritage included the utmost respect for those who gave their blood and their lives to fight for causes not their own.

Thousands upon thousands of men died in the firm belief that they were giving their lives for their comrades. They endured the hell of war for their brothers, their loved ones, and their nation.

It is no disrespect to say that, in some ways, perhaps they were the lucky ones. Those left behind to mourn their loss have to cope every single day with a huge person-sized hole in their hearts where there was once a living, breathing human being:

Those who gave their lives did not die in ways that we who are left behind, who have not served, can understand. We can perceive it, dimly, through the lens of history, but that lens is discoloured and inaccurate, because the reality is that the places where those men died actually looked pretty normal – at least, at first:

That strange banality of the places where so many died, and in the process hallowed the killing fields with their blood, is what makes the price that they paid so incomprehensibly high to those of us who have never served.

What is understandable to us is the fact that, without those sacrifices, the things that we love about America would not exist.

It is easy nowadays to write in trite phrases and patriotic words about honouring the fallen. It is much harder to do it. And it is getting harder by the day, too, because those men – and some women too – died for an idea, a nation.

That nation was built on their bones and nourished by their blood, and became the greatest, richest, freest, and most powerful that the world has ever seen. It became on balance a force for great moral good – and it was great because it was good.

And it was good because its people were good – especially those who pledged their lives, and far too often were required to honour that pledge in the most stark and terrible of ways, to defend their people and their nation:

America is free because its heroes gave their blood of their own free will. Let us not waste time quibbling over whether or not a soldier who was drafted into battle, and died, is somehow worth more or less than a volunteer who died in that same battle.

As it was once said by a great actor, “Ultimately, we’re all dead men. Sadly, we cannot choose how but we can choose how we meet that end – so that we may be remembered as men“.

Those men whose names adorn those thousands upon thousands of white markers in cemeteries across the nation met their ends as men. They died so that you could live. In the end, it is just that simple.

On a more personal note, there are several ex-military and Special Forces personnel who read my work and comment here. I am profoundly grateful for your presence. It is my personal honour and privilege to have you here, and though I am no longer in the USA and have not been for nearly a year now, it is still a nation that I love very much. I honour your sacrifices, and those made by your comrades who are no longer with you, in the small way that I can.

There will never be an end to war as long as humanity exists. It is not possible. War is the natural extension of politics and is, at best, its conclusion. While we cannot see an end to war, we can ensure that wars are fought for the right reasons – and that the most precious asset that a nation has, the blood of its fighting men, is not spilled for fruitless and meaningless causes.

2 Comments

You listen to certain members of the alt-right too much. We're too frigging geographically intertwined to break up even if we wanted to. We're not heading for a break up; we're heading for a civil war to make the last one seem mere.

But, as someone observed not too long ago, the United States tends to come out of its crises stronger then it was going into them. Just imagine a US short 5 or so million right wingers but in which _every_single_ left winger has been either destroyed or enslaved.

The Tranzis should tremble. A lot.

Good article.